Drawn from Nature

Shane and I fell in love in Key West. Oh - no, not with each other. That happened long before, at a garden center in Louisiana. That's a story for another day. In Key West, we found another, unlikely love.

We were on a business trip, actually, with some leisure thrown in. Of course, we enjoyed the hair-raising flight from Fort Lauderdale to Key West on a flying Volkswagen with seating for twelve. Who wouldn't? And then there was eccentric, beautiful Key West, itself a curious mix of wack-a-doodle and winsome. No wonder free spirits like Ernest Hemingway flocked there. Only in Key West is a five-toed cat anywhere near normal. Hemingway liked them, they say. Golf carts are the primary mode of transportation, aside from bicycles, in obligatory neon. Duval Street looks strikingly like New Orleans, and is similarly inclined to revelry. The homes, the history, the food - oh my! Swoon-worthy, all.

In Key West, you can be anybody, or nobody.

But that's not why we feel nostalgic about Key West. A few days in, we thought we had tasted pretty much everything that tiny island had to offer. But, no. By and by, we stumbled on the Audubon House, which happens to house Key West's Audubon House Gallery. And there, Shane and I ignited a new passion: The Birds of America.

Now, we knew about John James Audubon, because he schlepped through Louisiana on his famous (infamous?) bird hunt through America. Every Louisiana 4th grader takes a field trip to Oakley House, in St. Francisville, where Audubon lived briefly and worked as a tutor while merrily tromping through the woods, popping off birds to study and eventually draw.

Audubon was, by all accounts, quite a character. Born to a French sea captain and his mistress, little John was raised in France, a mischievous boy and known lover of nature. He fled to America as a young man, preferring the study of flora and fauna to becoming a minion in Napolean Bonaparte's considerable army. Equipped with not much more than clothes, pencils, and a curious mind, Audubon arrived at Mill Grove, a family-owned estate near Philadelphia in 1803. He was 18 years old.

He began, forthwith, a study of birds and their habitats, informally. It was Audubon who first experimented with bird-banding. He tied a string to the legs of Eastern Phoebes, and discovered they returned to the same nesting spot year after year. He married, and worked; sometimes as a tutor, and always a businessman. Audubon owned a dry goods store, and once was jailed for bankruptcy. Today, we might call him unscrupulous. Probably, he was just trying to pay the bills.

The problem was, John James Audubon was distracted. His true love; his one great passion, was birds. He was a self-proclaimed and -taught ornithologist in a brand new country with survival on the brain. America wasn't all that interested in Audubon's birds. Good thing he saw the bigger picture.

No pansy, John took out across our fair country, down the Ohio River to Kentucky, then out on the frontier, down the Mississippi River through Louisiana, Mississippi and the Gulf States, and eventually to the East Coast, meandering, studying, and drawing birds. He lived off the land. Hardy, guy, Audubon. Rugged. Curious.

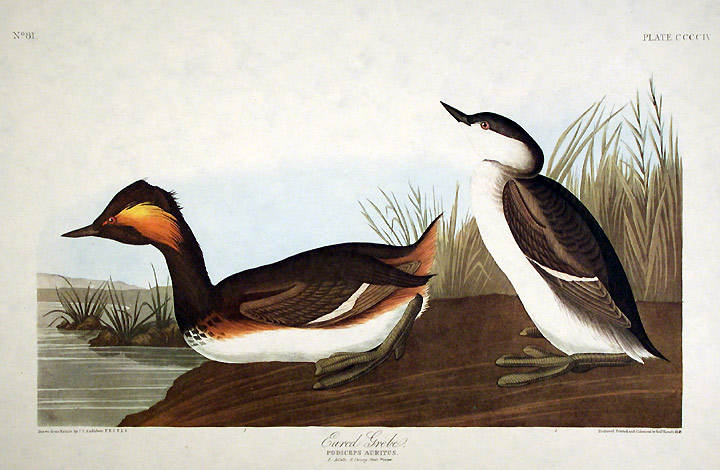

His methods were exacting, and maybe a little gruesome. John shot birds. Thousands of them, in fact. He shot them, and studied them, posing them in death as he had observed them in life. He wired them, and arranged them on his hand-made graph paper, so that, when drawn, they were to scale, their proportions accurate, and life-like. Audubon eventually seized upon a plan: he would record every bird in America, life-sized and in living color.

It took a while, and weighed, undoubtedly, heavily upon his marriage, from which he was absent months, and even years, at a time. A lesser man might have quit. Not John James Audubon. In 1826, collection in hand, he sailed to England, Mecca of pomp and circumstance, which gobbled up his Birds of America with an appetite befitting their corpulent king, George IV, patron of all things art and leisure.

Audubon finally published his dream - hand-colored, life sized birds, many in their natural habitat, printed from engraved copper plates - over twelve years, three publishers, and, including descriptive text, five volumes. The necessarily oversized paper, known as double-elephant folio, was 38x26 inches. Put that in your pipe and smoke it.

And that little history lesson brings me back to Key West, the Audubon House Gallery, and falling in love. Shane and I spent hours scouring the prints and lithographs, learning about the quirky and industrious Audubon, and his curious ornithology habit. We got (over) educated in the types of paper, sizes, printing methods, yada, yada, yada, that make Audubons valuable (or not).

Giddy, and feeling bit out of our element, we purchased our first print there: Carolina Parrots, which, incidentally, are now extinct. The parrots are, not the print, though the paper it's printed on is endangered, so to speak. Ours is a Princeton Edition, which means it's pretty high quality; a limited edition on archival paper.

It happens that Audubon actually foreshadowed extinction of some species in his later years, but it fell on largely deaf ears.

Over the years, we've added to our collection, dipping back into the familiar pool of that Key West gallery. Once, I accidentally bought some matted and framed Audubon duck prints at a consignment shop in Park City, Utah. I didn't stop to investigate; I just knew I liked them. A year later, I discovered my treasure.

Prints we've collected over the last 10 years, above

Shane and I were, and still are, drawn to the botanical quality of Audubon's birds. His work eclipsed other artists of the day, with good reason, and is relevant still. Audubon's works can be found in the best-dressed homes of the South. I love that it was important - tantamount even - to him to get every bird exactly right; an attention to detail to which only a fellow OCD sufferer can relate. I admire, too, Audubon's grit. He personally observed, shot (in the most loving and respectful way), and recorded every one of those 435 birds.

Fittingly, on each print, Audubon's epigram appears: Drawn From Nature by J.J. Audubon.